A Look Under the Hood of Venture Capital Firms

Some of my closest friends from law school, as well as students I barely know, really want me to stop talking about VC. So, naturally, I figured I would write an article on venture fund formation and compensation structure.

It seems like a very small percentage of people in the Midwest understand what venture capital is outside of knowing rich people in San Francisco invested in companies like Facebook and Uber. Hopefully this analysis of fund structure, obligations to Limited Partners (LPs), and compensation scheme will shine some light on the basics of venture funds.

Venture Capital Fund Formation

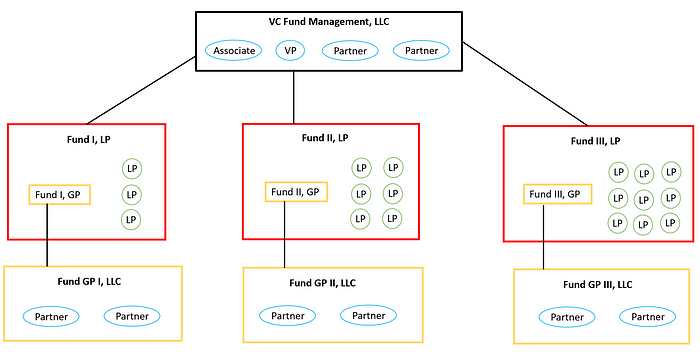

Venture capital firms are often housed by a management company formed as a Limited Liability Company to manage the firm’s operations across funds. Meanwhile, each fund is generally structured as a Limited Partnership to partition risk between funds. The Limited Partnership consists of LPs (investors) and the General Partnership (GP). The GP consists of the Partners running the fund and making investments out of the fund. To make matters more complex, the Partners will generally form an LLC, and that entity will become the GP of the LP to mitigate liability.

Did I confuse you yet? To make this a little easier to understand, see the diagram below.

VC Fund Management, LLC

The venture capital firm may operate under a [insert venture firm name] Fund Management, LLC. This entity is usually an LLC formed in the state where the firm is located. Fund Management hires the employees running the firm such as analysts, associates, principals, vice presidents, and partners. Each employee is paid their salary through this LLC, and other expenses such as office space come from this entity.

Funds as Limited Partnerships

Next, each fund (Fund I, Fund II, Fund III, etc.) is formed as a Limited Partnership, probably in Delaware due to better corporate law. This can be confusing because a Limited Partnership, which is the fund, is comprised of a General Partner (GP) and at least two Limited Partners (LPs). The individual LPs are investors in the fund that own a percentage of the fund depending on how much they invested. The Limited Partnership is called an LP, but each individual Limited Partner is also called an LP — yeah this part can be confusing but the easiest thing to do is just accept it and move on. Each fund forms its own separate LP to separate risk between funds.

For example, if someone is mad about Fund I, LP and sues the entity, the assets under Fund I, LP may be at risk, but the assets under Fund II, LP and Fund III, LP cannot be taken by the angry person suing. This way, the other two funds are protected from liability stemming from Fund I.

General Partners

As mentioned, each fund structured as a Limited Partnership requires a General Partner. The General Partnership consists of individuals on the investment team of the venture capital fund, usually the Partners in VC Fund Management, LLC. The General Partners are in charge of running the fund and making investments out of the fund.

General Partnerships have unlimited liability, meaning the Partners have a lot of risk of being sued if something goes wrong. So, to limit this risk, venture capital firms usually form a Limited Liability Company. The Partners are the members/owners of this LLC, and the LLC is listed as the General Partner for the fund. This is just how operators are able to limit their personal liability so someone suing the fund cannot take the Partner’s house, car, or other assets.

Limited Partners (LPs) aka Investors

The Limited Parters, as discussed above, are the investors. These can be high net worth individuals, corporations, family offices, fund of funds, pension funds, and more. As mentioned, not everyone can be an investor in a fund. You must be an accredited investor which is someone with a net worth exceeding $1M not including the primary residence, or someone making $200K per year or $300K per year if married. The Limited Partners generally do not invest on behalf of the fund or have any operational responsibilities. They generally just write the check to invest in the fund, pay management fees, and wait for money (hopefully more than they invested) to be sent back to them.

Limited Partnership Agreement

The Limited Partnership Agreement, or LPA, is the document governing each individual fund. This lays out the life cycle of the fund, type of investments that may be made, management fees (explained below), expectations of the GP, and rights of the LPs. As mentioned, the GP has a fiduciary duty to act in the best interest of the LPs when analyzing investment opportunities and making tough decisions such as ousting a founder or executive of a startup. The LPA will govern the operations of each individual fund, and may vary between funds depending on how the agreement was negotiated.

Compensation Scheme

The famous “2 and 20 Rule” is the standard for compensating fund managers. Venture capitalists don’t get rich off of their salary, they make their money on what is known as Carried Interest. The specifics of the relationship may vary, where a firm may actually charge a 2.5% management fee, the fee may come out of the $100M capital commitment, or fees can be charged on top of the capital committed — all of this will be clearly laid out in the LPA. This document also determines when and how LPs send money to the fund, usually through semi-annual capital calls. For the purposes of this example, we will assume the fees are paid on top of the capital committed.

First, let’s cover the “2”. Each LP, or individual investor, usually pays a 2% fee each year to the Management Company rather than to the Fund. So, if an investor invests $100K into Fund I, LP, they will pay $2K (100K*2%) every year to Fund Management, LLC. This 2% goes to pay salaries for the employees, office space, and other expenses. This fee is pretty high compared to alternative investments, but the goal is to repay this fee after returning capital to investors.

Now the fun part — the “20”. After the fund returns all of the investors’ capital, they have profit to distribute to the investors, but the General Partners usually keep 20% of this profit. So let’s break this down with an example:

Fund I, LP is a $100M fund. The fund invests in 20 startup companies, then after a few years all of those companies get acquired and the fund makes money. A 3x ROI (return on investment) is generally expected, so let’s say Fund I, LP now has $300M.

$100M is given back to the investors so they get their money back. Then, the investors are repaid the management fee (that 2% paid every year) so they have all of their money back. That number is $20M assuming Fund I, LP has been around for 10 years (2% of $100M is $2M; $2M*10 years is $20M). Now, Fund I, LP has paid $120M back to investors, leaving $180M in profit.

80% of the profit of $180M is distributed to investors which means $144M is paid out. However, Fund GP I, LLC keeps 20% (called Carried Interest) which is $36M. This $36M is distributed among the Partners in Fund GP I, LLC, which in my above example is 2 people.

So, both Partners make $18M each. Not a bad payday! Usually, some employees may own a small percentage of the Fund GP I, LLC so the Associate or VP may get 1–5%. Regardless, the goal is for a lot of money to be split between a small number of people.

Confused Yet?

Hopefully this analysis of corporate structure for venture capital firms and their compensation scheme was not too complicated. At the end of the day, there are more entities and agreements governing the operation of a venture fund than most people realize. I’m certainly still learning but the deeper you dive in the easier it gets to understand!

This is one law student’s research and analysis of venture capital formation. This is not legal advice and should not be taken as such.